History and stories

How it all started

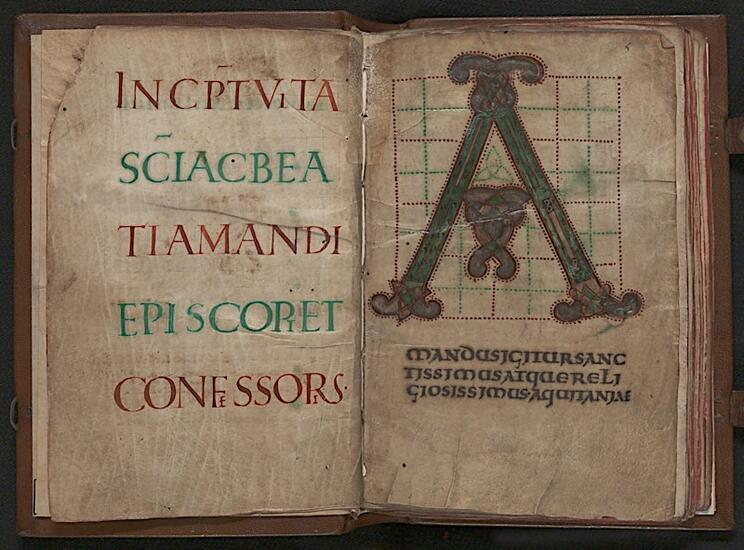

St Peter’s Abbey was established by the Christian missionary Amand. He came to Ghent in the seventh century AD by order of King Dagobert I. He preached Christianity and wanted to set up an abbey there. Eventually, he founded two of them.

St Peter’s Abbey was originally called Blandinium after its location on the Blandijn Hill. In the early years, the abbey admitted both men and women, but very soon the abbey definitively became a monastery. The other institute founded by Amand was a church, Ganda, which later became St Bavo’s Abbey. Since the tenth century AD, Blandinium has been known as St Peter’s.

The question as to which abbey was set up first caused a real feud between the two abbeys from the tenth century onwards. They both resorted to gross falsifications of history to prove their case.

The Vikings

St Bavo’s Abbey was by far the most prosperous of the two abbeys until the ninth century. Things changed with the invasion by the Vikings in the middle of that century. Face to face with the Danish army, the monks fled the abbey. The monks from St Peter’s Abbey returned much quicker than those from St Bavo’s Abbey. They took the opportunity to establish a dominant position for themselves in the ecclesiastical body of Flanders.

The fact that, from the ninth century onwards, the deceased members of the count’s family were buried at St Peter’s Abbey played a major part here. At the hands of Count Arnulf I of Flanders, St Peter’s Abbey emerged as the religious centre of the County of Flanders in the next century. Under his administration, it became a Benedictine Abbey. The prestigious relics which the count housed in the abbey certainly paid dividends.

The abbey and the sovereign

The importance of St Peter’s Abbey can be deduced from the way in which Ghent organised Joyous Entries for new sovereigns. After the coronation, each new sovereign travelled through the Netherlands. On this tour, the towns and cities gave honour to the sovereign, who, in turn, ratified their rights. This was how sovereigns safeguarded their positions of power. The sovereign’s first destination in Ghent was always St Peter’s Abbey. There, the sovereign received the sword of justice from the Count of Flanders and confirmed the rights and freedoms of the Abbey. Only then did the sovereign go into the city for the inauguration

The ceremonies in the abbey had a great symbolic value. The sovereign made it clear that he had received his authority from God and the abbey secured its privileged position. The Joyous Entries were celebrated with exceptional pomp. The scenario was more or less always the same.

The sovereign spent the night before the ceremony in the abbot’s castle in Zwijnaarde. In the morning, he made his way together with his cavalcade to the St Peter’s village. There, he was greeted by the highest clerics of the city. They accompanied him to St Peter’s Abbey where they were awaited by the abbot and his monks. Together, they attended a solemn mass in the abbey church. After the mass, the abbot girded the sword of justice from the Count of Flanders on the sovereign. The sovereign took an oath and they left the church. The day ended with a banquet in the abbey.

Between sovereign and city

The monks farmed the land to provide for their daily needs. St Peter’s Abbey possessed and exploited domains and entire villages even as far as in England. Moreover, it played a major part in Flemish cultivation, which converted woods, meadows, and marshes into fertile farmland in the twelfth and thirteen centuries. This way, a lot of abbeys acquired a huge patrimony of immovable goods. Donations from benefactors who wanted to absolve their defiled souls only served to increase that wealth.

Until the thirteenth century, St Peter’s Abbey played a key role in economic life. After that, it fell upon hard times. Unwise purchases and loans, famines, and an ambitious building policy brought the abbey to the verge of bankruptcy. Moreover, the Benedictines were now having less impact on society. New mendicant orders such as the Dominicans and Franciscans took over their mantle. Their active preaching and lifestyle had more feel for the challenges of an urbanising society.

The abbey became more and more the sovereign’s plaything. By appointing his minions as abbots, he acquired a decisive say in the allocation of taxes. As a result, the Ghent abbeys got themselves into trouble on more than one occasion during the city’s many conflicts with the landlord.

Purges and destructions

s early as the fifteenth century, people were protesting at the decay within the Roman Catholic Church. The publication by Martin Luther of his 95 theses signified the start of the Reformation in 1517 and Calvinism gained a large following in Flanders. Consequently, from the mid-sixteenth century onwards, the Netherlands were ruptured by a political and religious crisis. The abbeys came under severe attack. This had disastrous consequences for St Peter’s Abbey as well.

Conflict erupted in the summer of 1566. After the conclusion of a Protestant sermon, some twenty of the listeners forced their way into a cloister in the vicinity and smashed some religious images to pieces. The uprising spread throughout the Southern Netherlands like wildfire.

The iconoclasts didn’t spare Ghent either. They smashed altars, statues of saints, and stained glass windows to smithereens. St Peter’s Abbey was badly afflicted. The abbey chapel, the library, and the abbot’s residence were damaged. Once things had calmed down, repair work could begin.

In 1568, the Netherlands revolted against King Philip II. Ten years later, the Calvinists seized power in Ghent and occupied St Peter’s Abbey. That was the start of a second ‘purge’. The abbot and his monks fled to Douai. Calvinistic worship was given a place in the parish church next to the abbey, but the abbey church had to pay a heavy price. The Calvinists wanted to sell the abbey buildings and use the proceeds from the sales to finance new city walls.

However, the process never got that far. In 1584, governor Farnese brought Calvinistic Ghent to its knees. The Benedictines returned. The once so mighty St Peter’s Abbey was by then little more than a ruin. The abbey church and the dormitory were destroyed and partly demolished, the abbot’s residence and the deanery were severely damaged, and the library had been plundered.

An abbey fit for royalty

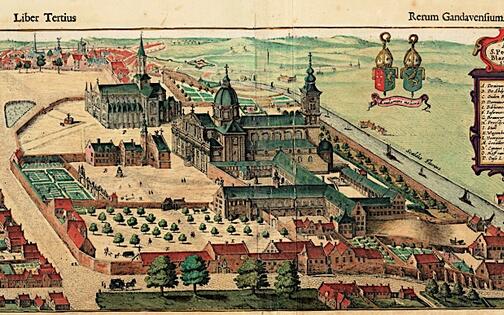

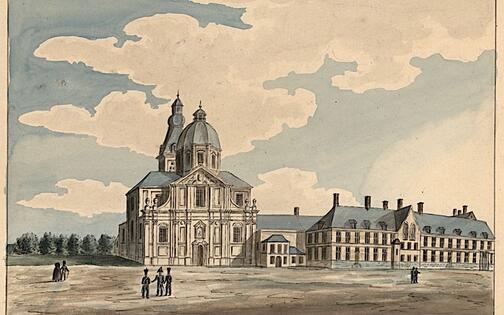

The reconstruction of St Peter’s Abbey was a burdensome assignment. It was not until the first quarter of the seventeenth century that the financial recovery and material restoration took shape. The new abbey church, based on the model of St Peter’s Church in Rome, was the crown gem. The work took almost a whole century to complete.

From the seventeenth century onwards, Ghent witnessed a strong upturn in Roman Catholicism. Nevertheless, St Peter’s Abbey was still plagued by financial and disciplinary problems. It was not until the appointment of abbot Musaert in 1720 that things started to improve. The abbey became the ideal meeting place for conventions, ceremonies, and banquets. Prominent figures who had an influence on the abbey had to be received in style. And so, the building developed into a royal residence to vie with the castles or city palaces of nobles and wealthy citizens. It included luxurious abbot’s quarters with ornately decorated interiors, a greenhouse, and an orangery.

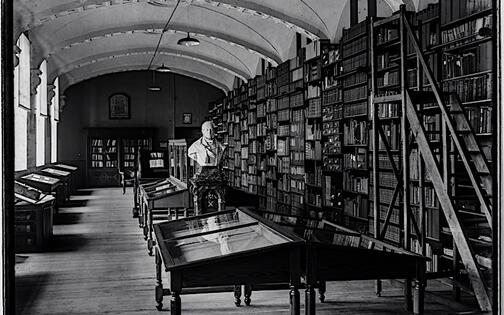

After that, abbot Philip Standaert had the refectory and the library completely redesigned in line with eighteenth century taste. His successor, prelate Gudwalus Seiger, nicknamed The Magnificent One (‘Le Magnifique’) also had grandiose building plans. He built a new infirmary in classic style. At that time, St Peter’s Abbey was the wealthiest abbey in the Netherlands.

An abbey fit for royalty

Abbot Martin van de Velde succeeded Gudwalus The Magnificent in 1789, the year of the Brabantine Revolution. The Southern Netherlands rebelled against the Austrian authority of Emperor Joseph II, and once again St Peter’s Abbey came under heavy attack. Sadly, the recapture of power by the Austrians a year later brought no relief.

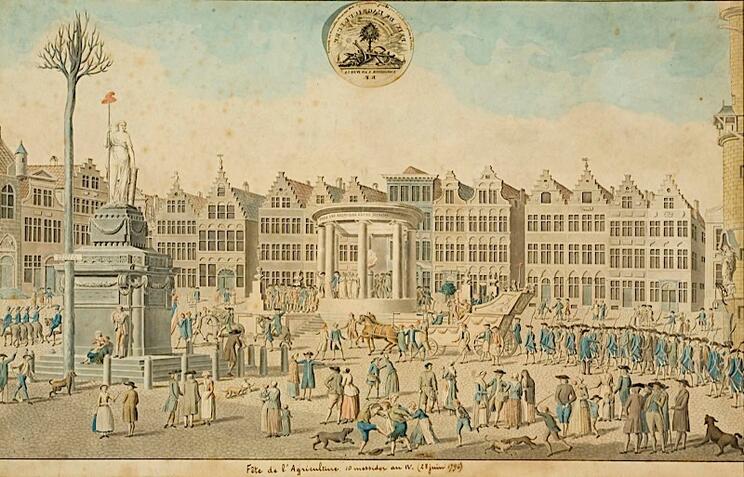

The French drove away the Austrians and entered Ghent in 1792. Eventually, they subdued all religious institutions with a single stroke of a pen. The 31 monks of St Peter’s Abbey had to leave in 1796 and were no longer allowed to wear cloister cloth. All goods became state owned. That was the finale in a slow process of social changes which strongly reduced the power of cloisters.

And then?

The Abbey church was put to a different use in 1798. In the next ten years, it served as the Musée du Département de l’Escaut, the forerunner of the Museum of Fine Arts. From 1803, it was made partially available again for Roman Catholic worship. From then on, the church was called Our Lady of St Peter’s Church. The library was transferred to Baudelo Abbey in 1798. After that, it moved to the Ghent University Library, which still houses valuable works.

The Abbey and the city

The other abbey buildings did not enjoy such good fortune. Ghent City Council bought them in 1810 and converted them into an army barracks. The parish church, the luxurious abbot’s quarters, and the deanery with the prison were demolished to make way for a military training area. In 1849, the Abbey square took on its present form according to the design by architect Charles Leclerc-Restiaux. On the site of the present gardens, they erected stables, latrines, and other utility buildings for military activities.

By 1948, thankfully, the abbey’s days as an army barracks were over. The city council wanted to restore St Peter’s Abbey and give it a cultural function. The military buildings in the gardens were demolished.

A long-term effort

The abbey buildings did not benefit from their time as an army barracks. The courtyard was divided up into boxes, the window tracery virtually disappeared, the chapter room was enclosed in mason, the mortuary was given an entire floor, etc. Works carried out in the fifties and sixties were also very radical. Work started first on the restoration of the courtyard. The chapter room was restored before 1958.

The eighteenth-century library, once the pride of the abbey, was beyond repair. One appealing upper room of valuable manuscripts and books was converted into two rooms on the first and second floors, one on top of the other.

After 1958, work was carried out on the refectory and the old kitchen in the western wing. During the course of the sixties and seventies, work followed on the eighteenth-century infirmary (now the Huis van Kina, a nature museum), the wine cellar, and the lofts. The restoration of the refectory wing was the final part of the extensive campaign designed to safeguard St Peter’s Abbey from further decay.