History and stories

It was a wooden square construction with a main building of two floors and a few outbuildings, including a grain store. This soon became the new hub for trade and industry in the region. Ghent developed into the biggest city of the brand-new Flanders.

Alterations

In the eleventh century, the wooden structure was replaced by a luxurious residence in costly Tournai limestone. The nearby wooden outbuildings served as warehouses, where yields from the count’s domain from the nearby region were gathered and processed by artisans. In the next century, the castle became a moated castle. An embankment about three metres high was constructed around the building. The once first floor thus became the ground-floor level. A stone wall was also built around it. From then on, a gatehouse separated the inner bailey from the outer bailey, which we now know as Sint-Veerleplein.

The Alsace family

In the twelfth century, Theoderic of Alsace became Count of Flanders. During his rule, and later that of his son Philip, the Flemish cities, especially Ghent and Bruges, became major pawns on the political landscape of the County of Flanders. Thanks to its wool industry, Ghent developed into a thriving city in that period. From then on, wealthy traders lived in luxurious stone houses made of Tournai limestone. It was their way of showing off their importance. In response to these ‘Stones’, when Philip of Alsace returned home from his first crusade, he immediately issued the assignment to convert the Count’s Castle to an imposing stone castle, which was designed, according to one contemporary chronicle, ‘to curb the arrogance of the people of Ghent’.

Crac des Chevaliers?

Philip therefore had the moat raised and extended. The central building became a 30m-high tower, which was also altered inside. Around the upper garden, he erected a wall with 24 watchtowers and a protruding gatehouse, which still bears the following inscription: ‘This castle was built in the year 1180 AD by Philip, Count of Flanders and of Vermandois, son of Count Theoderic and Sibylla’. Various types of bricks were used in order to obtain a multicoloured architecture with a richer look. Otherwise, the decoration stayed quite modest. The structure of the fortress reminds us of the famed Crac des Chevaliers, the renowned fortress in Northern Syria, which is inextricably linked with the crusades. Philip might have drawn some inspiration from it.

A court of law

The Count’s Castle was never a permanent residence. Only when the count’s household was in Ghent did they actually stay in the castle. In any case, the city was not really the count’s favourite residence. He felt the people of Ghent were far too rebellious. In fact, the fortress was mainly the administrative centre of the county. The count’s administrative office was located there and it was also a law court.

From the fourteenth century, the Castle of the Counts became the epicentre of justice in Flanders. The Council of Flanders, which, among other things, was authorised to judge serious crimes and lese-majesty and served as the court of appeal, established itself there. In the seventeenth century, there were four different courts in operation in the castle.

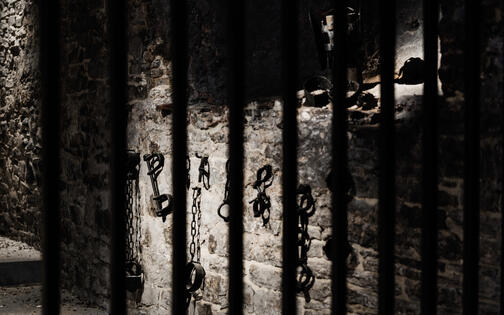

Theatre of horror

As well as being a law court, the Castle of the Counts was also a prison. The semi-underground cells which it housed were damp and draughty and very cold, particularly in winter. The underground dungeons were the most feared, as, of course, was the torture. Although the legal procedure for torture in the early Middle Ages died a quiet death, it was reintroduced at the time of the Council of Flanders. From the fifteenth century onwards, torture and ‘harsh interrogation’ such as flogging and removal of limbs were once again far from unusual.

-

© Marthe Hoet -

© Marthe Hoet -

© Marthe Hoet -

3 Show all photos

Textile factory

When the court relocated in the eighteenth century, the building was auctioned. The proceeds were set aside to fill Austrian and French state coffers respectively.

Architect Jean-Denis Brismaille purchased the first plot. He built a residence fit for a director next to Castle of the Counts’ entrance gate. He converted the fortress into an industrial complex which housed cotton mills and a metal construction workshop. On the free land of the fortress, he built dwellings for some fifty workers’ families. The second plot became the property of Ferdinand Jan Heyndrickx, industrialist and brother-in-law of Lieven Bauwens. He, too, opened a cotton mill. The old medieval castle did not look so very different from Ghent’s other typical working class districts. Only the old entrance gate served as a reminder of its medieval past. From then on, the Castle of the Counts was known as the Cité Hulin, after the son-in-law of Jean-Denis Brismaille, who then owned most of the houses in the Castle of the Counts.

The medieval castle as a residential district?

At the end of the nineteenth century, the companies moved to the outskirts of the city. There were those who wanted to see the dilapidated building demolished and sold as building land. Fortunately, there was no interest in the project, so Ghent City Council and the Belgian government bought back the site in several stages from private ownership. For the following restoration, architect Jozef De Waele opted for a romantic interpretation of Philip of Alsace’s castle. From 1907, the Castle of the Counts was open to the public. The World Exhibition in 1913 launched the building’s reputation as Ghent’s biggest tourist attraction.

-

Ontmantelingswerken Gravensteen in 1888 - 1897: zicht op de Donjon vanop het opperhof (zuidgevel en deel van de westgevel zijn afgebroken) (c) Stadsarchief Gent -

Restauratiewerken aan het Gravensteen in 1894-1909 (c) Stadsarchief Gent -

De Groentemarkt op het Sint-Veerleplein met op de achtergrond het Gravensteen in restauratie, ca. 1892/1893, Foto Arnold Vander Haeghen, Gent, Huis van Alijn -

Het Gravensteen tijdens de restauratie, ca. 1900, Foto Edmond Sacré, Gent, Stadsarchief -

Zicht op het Sint-Veerleplein en het Gravensteen, 1909, Foto Edmond Sacré, Gent, Stadsarchief -

5 Show all photos