Rehabilitation of the Ghent victims of witch-hunting

Why rehabilitation?

Now, 400 years later, victims of witch-hunting in Ghent are finally getting the rehabilitation and attention they deserve. Their persecution and the delusion that underpinned it are a dark chapter in Ghent’s history.

Although the fear of diabolical magic may seem far removed from our contemporary society, a focus on witch-hunting is still highly relevant today. Just like elsewhere in Europe, belief in witchcraft in Ghent peaked in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries: a tumultuous period of war, climate change, religious conflicts and famine. In times of crisis and uncertainty, people are more susceptible to irrational explanations. Societies going through hard times seek scapegoats. During this period, they found just that in so-called witches.

We too are confronted with wars, climate change, economic crises and other challenges; and rumours, prejudices and disinformation also continue to be rife. The scapegoat mechanism is very much alive today. So the mirror held up to us by the historical persecution of witches teaches us valuable lessons in the here and now.

How did witch-hunting begin?

The belief in magic and supernatural phenomena has a long history. Fortune tellers and women with magical powers were already the subject of myths in Classical Antiquity. The spread of Christianity did not prevent popular superstitions and the use of spells and magical herbal remedies from remaining deeply entrenched in everyday life. The few witch executions that took place in the Middle Ages seem to have sprung more from spontaneous popular anger than from formal legal proceedings.

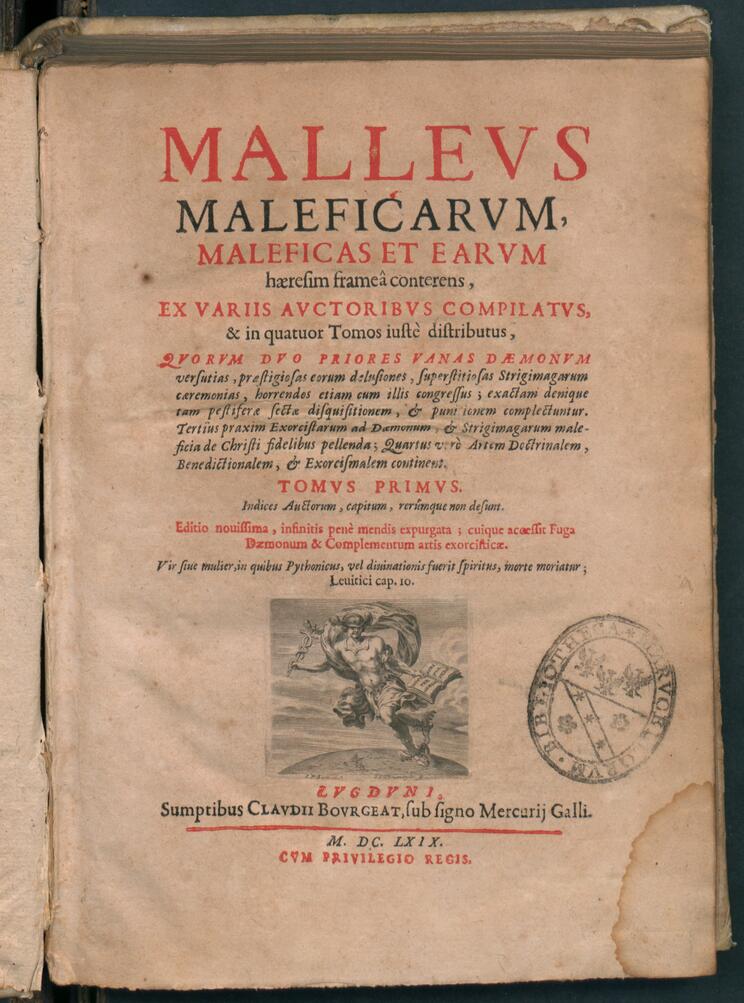

It was not until the end of the fifteenth century that the situation changed. A growing number of demonologists penned inflammatory tracts in which witches were described exclusively as women. The emergence of the printing press allowed these tracts to be disseminated. The Malleus Maleficarum or the ‘Hammer of Witches’ from 1486 is one of the most misogynistic books ever written and became a hugely successful bestseller. This book describes how witches should be identified and punished.

The title Malleus referenced earlier works intended to combat heresy, such as the fourth-century Malleus Haereticorum, or the ‘Hammer of Heretics’, and the fifteenth-century Malleus Judaeorum, or the ‘Hammer of Jews’. However, the focus on women was new.

What were the underlying causes of witch-hunting?

In the late sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, our region had to reckon with a colder and less favourable climate. This period was subsequently dubbed the Little Ice Age. The harsh winters brought poverty, failed harvests and famine. Witches were blamed for everything going wrong.

At the same time, there was prevailing religious unrest. Deep dissatisfaction with the Catholic Church was giving rise to more and more religious separatist movements. These were characterised by a narrow focus on the movements’ own beliefs, and little tolerance for those with different views. The Catholic Church was also becoming more dogmatic. In addition, there was a great deal of fear and uncertainty amongst the population about the best way to reach heaven.

Who are these witches?

In early modern Europe, 80% of convicted witches were women. This was also the case in the county of Flanders. The Ghent records reveal a ratio of 75% women compared to 25% men. Women often failed to meet the dominant patriarchal societal image of the ideal woman: young, fertile and married. Allegations of witchcraft affected mainly older women, or women living in poverty, but also widows or outspoken women.

Yet not every witch conformed to the cliché of the marginalised beggar on the periphery of the village. Indeed, this is a cliché that continues to this day. Consider the figure of the witch in numerous films and cartoons, for example. Flemish witches also counted married and well-to-do women among their number. And men too. The latter generally failed to live up to the prevailing ideals of masculinity, engaged in practices such as divination, or had witchcraft added to other charges as a secondary accusation.

The allegation and prosecution of witchcraft were often the result of a complex combination of specific factors and circumstances. Age, social class, family ties, individual personality and cultural and geographical differences all played a role. Yet it is beyond dispute that it was mainly women who were accused of witchcraft and prosecuted for it. So gender was not an exclusive factor, but was often a decisive one.

Witch-hunting in The Low Countries

In the Netherlands, the authorities initially took a somewhat hesitant approach to popular belief and superstition. The penalties imposed were relatively mild and ranged from fines to mandatory pilgrimages. From around 1450, isolated cases of witchcraft gradually became more frequent. It was not until the end of the sixteenth century that large-scale witch-hunting became widespread.

However, there were huge geographical differences. In the Northern Netherlands, the modern-day Netherlands, sweeping witch-hunts remained relatively rare. Between 1450 and 1608, around 160 people were executed. In the Southern Netherlands, roughly speaking modern-day Belgium, the belief in witchcraft appears to have been more deeply rooted. An estimated 1150 executions for witchcraft took place. In the county of Flanders alone, there were around 200 death sentences. It is also notable that some years were more gruesome than others.

In his battle against ‘heresy’, King Philip II promulgated the so-called witchcraft law in 1592 in the Southern Netherlands. This defined witches as the worst and most dangerous kind of heretics. Bishops and priests were encouraged to remain vigilant and to eradicate evil. From 1595, witches were burned at the stake with increasing frequency.

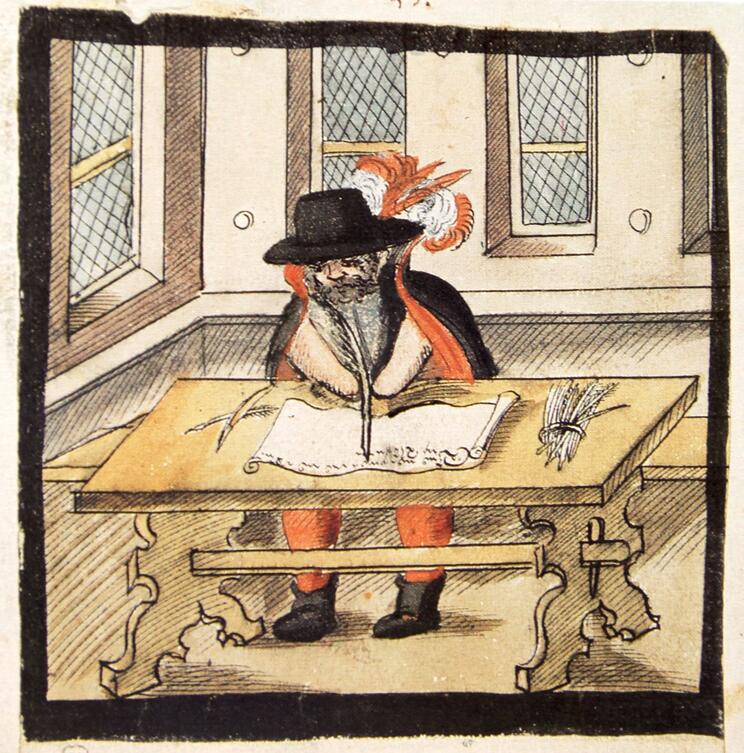

The driving force behind this law was the Flemish Jesuit and expert in demonology, the originally Spanish Martin del Rio. In 1599 he published Disquisitiones Magicae or ‘Investigations into Magic’. This book was soon a bestseller, and became the ultimate handbook for fighting witchcraft in the Netherlands.

Following the death of Philip II during the reign of the Archdukes Albert and Isabella (1598-1621), peace and prosperity returned to our regions. Strikingly enough, Ghent’s witch-hunting reached a pinnacle in the years 1601-1604, while elsewhere in our region the peak only came in around 1630-1645. It would seem that periods of relative calm created an appetite for reckonings.

It appears that witch persecution was more of a phenomenon in rural areas, especially in sparsely populated ones, and places with less developed legal structures. However, the cities were not spared either. The pyres did not die out until the late seventeenth century.

Witch-hunting in Europe

To map all the European witch trials is still an extremely challenging task. Historians estimate that between 45,000 and 60,000 people died as a result of the witchcraft delusion. But this delusion was not equally prevalent everywhere in Europe.

One possible cause for the major geographical differences is the degree of religious strife and uncertainty being experienced at the time. Countries and regions with a near-uncontested dominant religion saw a noticeably smaller prevalence of the witchcraft delusion.

There were local hotbeds in southern Germany, Poland, Scandinavia, Scotland, Switzerland, France and the Southern Netherlands. Yet Ireland, Italy and the Iberian Peninsula seem to have been hit much less hard.

The ins and outs of a witchcraft trial

Witchcraft trials started with rumours and gossip. Antisocial behaviour, adultery, suicidal tendencies, inappropriate talk, involvement in human or animal illness or death, or simply contact with an alleged witch could be cause for suspicion. Once someone had the ‘fama’ [reputation] of being a witch, it was very likely that he or she would actually be charged as such. The injured party or the authorities could then take criminal action. Sorcery, nocturnal gatherings (witch sabbath) and ‘carnal conversation’, or copulation with the devil, were the most common charges. Witches were suspected of having made a pact with the devil to wreck society.

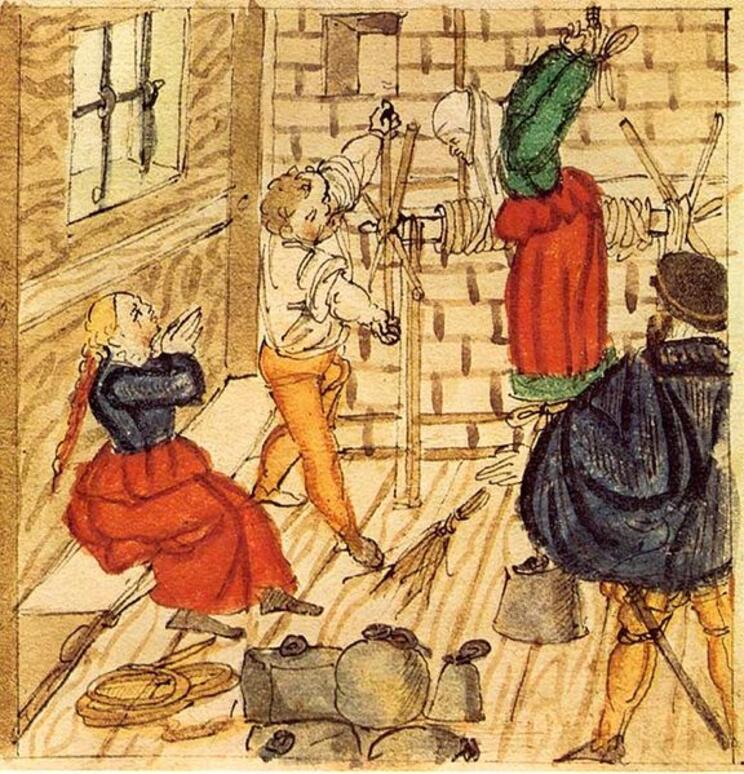

Just like other serious crimes, the crime of witchcraft was dealt with inquisitorially. Criminal judges were responsible for determining whether someone was a witch and bore the burden of proof themselves. This also explains their often harsh approach during interrogation. Evidence was usually obtained from the testimonies of two reliable witnesses or the suspect’s confession. The former often proved tricky, because witnesses who had spread rumours for fear of being accused themselves were often reluctant to repeat their allegations in court. In many cases, the suspect’s confession was the only way of proving guilt. In order to obtain this, judges resorted to the rack. So interrogation under torture was often the next step.

Boudewijn Waelspeck, who hailed from Ypres, was an infamous witch executioner in Ghent. He worked his way up and found employed with the Council of Flanders in Ghent. He had a far-reaching reputation as someone who rapidly obtained confessions with dreadful torture methods, such as thumb screws and a collar with pins. His popularity ensured that he was also deployed elsewhere in Flanders to force suspected witches to confess. He demanded considerable sums for his services and, just like some judges, was not immune to bribes from the victim’s family.

Between 1601 and 1604, at least ten Ghent women confessed that they had had ‘carnal conversations’ with the devil. One died whilst being tortured in the Gravensteen, and eight women and one man were burned at the stake. The executions generally took place on Sint-Veerleplein, but sometimes also on Vrijdagmarkt. Burning at the stake was the most common execution method, due to the supposedly purifying effect of the fire.

Cases in Ghent

Catherine Tancré

Catherine was interrogated following a complaint from a passer-by in 1603. While she was begging on Oudburg, a child walking past her dropped a piece of bread. Catherine picked it up, but the child refused to take the bread back. Irritated, the old woman mumbled: ‘May the devil take you.’ This statement was to prove fatal for her, because shortly afterwards the child fell ill. The Ghent beggar was found guilty and burned at the stake in 1603.

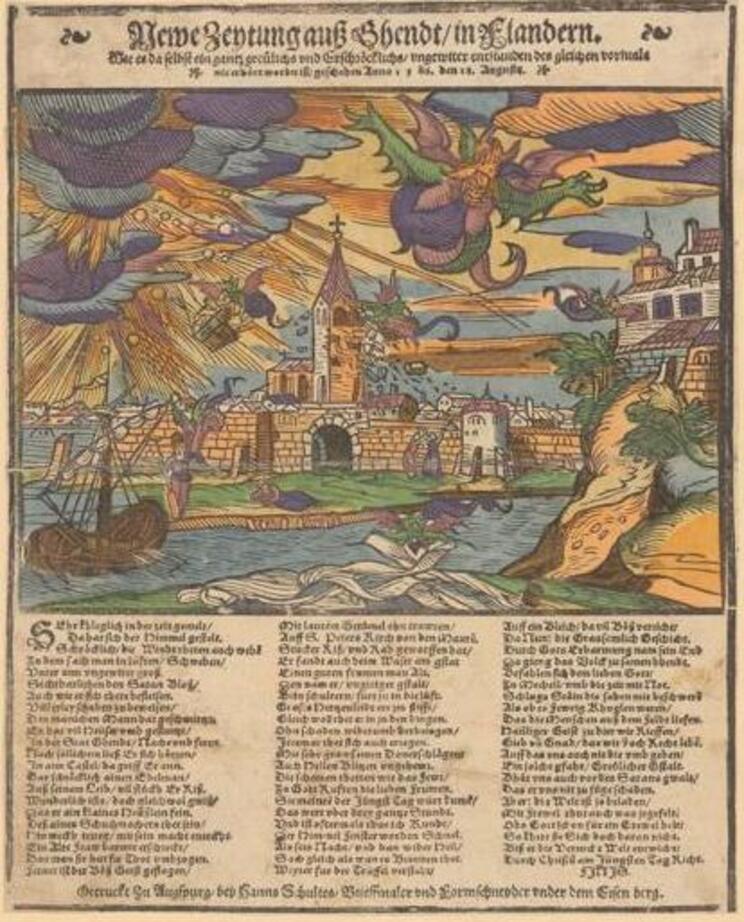

Chrystine Kints (The Ghent Tower Fire)

On 2 September 1602, a terrible thunderstorm began at ten o’clock in the evening in Ghent. The flash of lightning that encircled the spire of St. John’s Church resembled a torch. Following an enormous thunderclap, the tower burst into flames. The rumour spread that the devil had collected witches and brought them to Ghent. Even the archducal couple Albert and Isabella, who were staying in Ghent at the time, confirmed the story. These sensational tales of flying arsonist witches spread rapidly. The rumours reached Harelbeke, where Chrystine Kints was suspected of witchcraft. On 28 January 1603, she was interrogated under torture and confessed to all charges, including the arson in Ghent. On Whit Sunday 1603, Chrystine was burned alive in Harelbeke.

The destruction of church towers was a recurring theme in accusations of witchcraft. As early as 1565, Pieter Bruegel the Elder made an engraving with a church tower being destroyed by dragons and wizards in the background. Sixteen years prior to the events in Ghent, the story made ‘headlines’ in Germany! In 1586 a pamphlet was printed in Augsburg with a story about ‘evil spirits’ who were destroying Ghent church towers. An early example of fake news...

Tanneken van Meldere

While begging on Oudburg, Tanneken met the devil in the guise of a black dog. He ordered her to make a child sick. In her interrogation, Tanneken admitted that she had had four ‘carnal conversations’ with the devil. She died in the Gravensteen prison on July 3, 1608.

Cornelia Van Beverwyck

In 1598, Cornelia, also known as ‘barefoot Nele’, was found guilty of ‘intercourse with Satan in broad daylight in Ekkergem’. Following this event, the old woman made at least five people sick on Muide and Kalandenberg with herbal mixtures. Two of them did not survive. Cornelia was condemned as a ‘sorceress’ on 14 July 1598. She was burned at the stake. All her possessions were confiscated.

Annekin van Laerne

Annekin was a blind man who earned a living as a soothsayer. In 1527 he was accused of having struck a pact with the devil. Annekin confessed under torture. The man was freed, but was not permitted to leave the city. He was branded on the cheek with a glowing poker and was obliged to beg forgiveness from the city council. Every Thursday he attended mass in St John’s Church and lit a candle there.

In the end, all this was of little benefit. Seven years later, on 29 May 1534, Annekin was rearrested, his head was shaved, and he was beheaded on Veerleplein.

A fitting location for a memorial plaque

The memorial plaque for the victims of witch persecution is affixed to a wall near the Donkere Poort [Dark Gate], a former gatehouse of the so-called Prinsenhof, where Emperor Charlemagne was born. Hanging beneath the gate today are the names of all Ghent residents who were beheaded or burned at the stake in the time of Emperor Charlemagne.

The memorial plaque for the victims of witch persecution hangs on the neighbouring wall of CAW Oost-Vlaanderen, which has been providing shelter for the homeless in Ghent for many years.

CAW Oost-Vlaanderen offers temporary shelter to those without a roof or a home, with an emphasis on self-determination and maintaining connections with life outside the shelter, supported by professional guidance. People become homeless for a variety of reasons, including relationship problems, financial difficulties and generational poverty. Society imposes expectations that are impossible for everyone to meet. Those who do not live up to these expectations can fall behind, with serious consequences.

The homeless are often viewed as scapegoats. They are blamed for their own problems, whilst it is in fact society’s responsibility to guarantee the wellbeing of all. We must take joint responsibility to prevent the creation and marginalisation of scapegoats.

Lespakket Heksenstreek

Nu de stad Gent de slachtoffers van heksenwaan eerherstel en erkenning biedt in de vorm van een gedenkplaat hebben we een lespakket ontwikkeld over dit thema in samenwerking met Learning Design Studio Oetang.

We mikken in de eerste plaats op leerlingen uit de 2de graad secundair onderwijs, waar heksenvervolging aan bod komt in de les geschiedenis. Maar we zien het breder en vinden dat dit lespakket ook perfect past binnen andere vakken zoals gedrags- en cultuurwetenschappen, zedenleer, filosofie…

![From: Ulrich Molitor, De Lamiis et pythonicis Mulieribus [‘On Witches and Female Soothsayers’] (1489) Wikimedia Commons.](/sites/default/files/styles/gallery_single/public/2023-10/12.%20Ulrich_Molitor_Von_den_Unholden_Teufelsbuhlschaft_verleiding%20duivelspact_0.jpg?itok=aculU48A)